I keep seeing articles about what should be a planet and what should be a dwarf planet. Looking at what the current rules are, a planet must have "cleared out neighborhood around its orbit". I would think that Mercury is a dwarf planet. I think that Mercury didn't clear its neighborhood, the Sun did. I would surmise that if Mercury was in Pluto's current orbit, the debris in and around the orbit would still be there.

Planets and Dwarf Planets

- Thread starter IQ=>1

- Start date

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Physics can serve well here. Indeed, a physicist (Jean-Luc Margot), did a paper on this a few years ago shortly after the Pluto uproar.

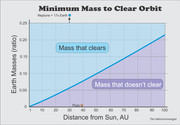

Here is a chart that shows the minimum mass necessary to clear an orbit. Notice that it takes very little mass close to the host star but much more mass as distance increases.

The time frame for those calculations would be part of any debate whether or not to adopt this model. I think he uses 1 billion years, which seems logical.

[Added: I fixed a label and corrected the spelling for heliochromologist, which I tend to misspell. ]

]

Here is a chart that shows the minimum mass necessary to clear an orbit. Notice that it takes very little mass close to the host star but much more mass as distance increases.

The time frame for those calculations would be part of any debate whether or not to adopt this model. I think he uses 1 billion years, which seems logical.

[Added: I fixed a label and corrected the spelling for heliochromologist, which I tend to misspell.

Last edited:

Looking at the chart that is provided, and knowing Mercury averages .4 AU, I think Mercury didn't clear its orbit. The gravitational pull from the Sun more than likely pulled all the smaller objects in and around Mercury into itself. Then again, Earth, Mars, Jupiter, and Neptune haven't cleared out their respective neighborhoods either. So, I would imagine the best argument would be to redefine the term planet?

Yes, the favored model is that planetismals aggregated into planets.Looking at the chart that is provided, and knowing Mercury averages .4 AU, I think Mercury didn't clear its orbit. The gravitational pull from the Sun more than likely pulled all the smaller objects in and around Mercury into itself.

The orbital debris in these orbits are temporary, though Trojans are far more secure. The chart reveals what mass is required to eventually clear an orbit. Some objects come and go. Earth has at least one that is hanging around...but it will be cleared out over a relatively short time.Then again, Earth, Mars, Jupiter, and Neptune haven't cleared out their respective neighborhoods either. So, I would imagine the best argument would be to redefine the term planet?

Physics has great mastery over the gravitational laws, thus should be used if, indeed, orbital clearing is to be part of the criteria for planethood. Without it, we will have hundreds, IIRC, of new planets.

Catastrophe

"Science begets knowledge, opinion ignorance.

Helio is, as usual  , quite correct.

, quite correct.

"Without it, we will have hundreds, IIRC, of new planets."

In general, there is an exponential type relationship between size and population.

There is no "fixed" relationship in Nature between planet, dwarf planet, asteroid, meteoroid, and dust particle. Definitions are purely our semantic problem. It would be ludicrous to name dust particles. We draw the lines.

By our definition, Mercury (capital M please) is a planet. It matters not a jot that whether we call it a planet or dwarf planet. Actually Mercury's orbit was cleared by the collision between proto Mercury and another large body. Mercury is the overgrown core which resulted.

The need for clarification in nomenclature arose when we started finding Pluto-sized bodies in the outer Solar System. Can we live with ten, one hundred, one thousand, ten thousand, small "planets"? Of course not. Answer - re-classify.

For the record, the sizes of bodies in the Solar System, in decreasing order, are:

Sun (star)

Jupiter (planet) (gas giant)

Saturn (planet) (gas giant)

Uranus (planet) (ice giant)

Neptune (planet) (ice giant)

JSUN owe their size to presence of hydrogen and helium.

Earth (inner planet)

Venus (inner planet)

Mars (inner planet)

Ganymede (moon of Jupiter)

Titan (Moon of Saturn)

Mercury (inner planet)

Callisto (moon of Jupiter)

Io (moon of Jupiter)

Moon ((moon of Earth))

Europa (moon of Jupiter)

Triton (moon of Neptune)

Eris (trans Neptunian object)

Pluto (trans Neptunian object)

Cat

"Without it, we will have hundreds, IIRC, of new planets."

In general, there is an exponential type relationship between size and population.

There is no "fixed" relationship in Nature between planet, dwarf planet, asteroid, meteoroid, and dust particle. Definitions are purely our semantic problem. It would be ludicrous to name dust particles. We draw the lines.

By our definition, Mercury (capital M please) is a planet. It matters not a jot that whether we call it a planet or dwarf planet. Actually Mercury's orbit was cleared by the collision between proto Mercury and another large body. Mercury is the overgrown core which resulted.

The need for clarification in nomenclature arose when we started finding Pluto-sized bodies in the outer Solar System. Can we live with ten, one hundred, one thousand, ten thousand, small "planets"? Of course not. Answer - re-classify.

For the record, the sizes of bodies in the Solar System, in decreasing order, are:

Sun (star)

Jupiter (planet) (gas giant)

Saturn (planet) (gas giant)

Uranus (planet) (ice giant)

Neptune (planet) (ice giant)

JSUN owe their size to presence of hydrogen and helium.

Earth (inner planet)

Venus (inner planet)

Mars (inner planet)

Ganymede (moon of Jupiter)

Titan (Moon of Saturn)

Mercury (inner planet)

Callisto (moon of Jupiter)

Io (moon of Jupiter)

Moon ((moon of Earth))

Europa (moon of Jupiter)

Triton (moon of Neptune)

Eris (trans Neptunian object)

Pluto (trans Neptunian object)

Cat

Yes, that's a great point. There is a power law that makes the number of smaller objects exponentially larger. This is especially true when the large ones are in an environment where they can collide and make smaller fragments.In general, there is an exponential type relationship between size and population.

There is no "fixed" relationship in Nature between planet, dwarf planet, asteroid, meteoroid, and dust particle. Definitions are purely our semantic problem. It would be ludicrous to name dust particles. We draw the lines.

The likely number of dwarf planets in the Kuiper Belt are about 200, but beyond that the estimate is about 10,000. If Planet 9 is found, that number might jump even higher. [Wiki info here.]The need for clarification in nomenclature arose when we started finding Pluto-sized bodies in the outer Solar System. Can we live with ten, one hundred, one thousand, ten thousand, small "planets"? Of course not. Answer - re-classify.

Catastrophe

"Science begets knowledge, opinion ignorance.

Helio is, as usual, quite correct.

"Without it, we will have hundreds, IIRC, of new planets."

In general, there is an exponential type relationship between size and population.

There is no "fixed" relationship in Nature between planet, dwarf planet, asteroid, meteoroid, and dust particle. Definitions are purely our semantic problem. It would be ludicrous to name dust particles. We draw the lines.

By our definition, Mercury (capital M please) is a planet. It matters not a jot that whether we call it a planet or dwarf planet. Actually Mercury's orbit was cleared by the collision between proto Mercury and another large body. Mercury is the overgrown core which resulted.

The need for clarification in nomenclature arose when we started finding Pluto-sized bodies in the outer Solar System. Can we live with ten, one hundred, one thousand, ten thousand, small "planets"? Of course not. Answer - re-classify.

For the record, the sizes of bodies in the Solar System, in decreasing order, are:

Sun (star)

Jupiter (planet) (gas giant)

Saturn (planet) (gas giant)

Uranus (planet) (ice giant)

Neptune (planet) (ice giant)

JSUN owe their size to presence of hydrogen and helium.

Earth (inner planet)

Venus (inner planet)

Mars (inner planet)

Ganymede (moon of Jupiter)

Titan (Moon of Saturn)

Mercury (inner planet)

Callisto (moon of Jupiter)

Io (moon of Jupiter)

Moon ((moon of Earth))

Europa (moon of Jupiter)

Triton (moon of Neptune)

Eris (trans Neptunian object)

Pluto (trans Neptunian object)

Cat

These are, of course, just the largest ones. They are followed by (in various miscellaneous orders)

Dwarf planets, where not duplicated (e.g., Ceres = asteroid)

Other planetary moons

Asteroids

Trans Neptunian Objects (TNOs)

Meteoroids

Any categories I have missed, down to

Interstellar and interplanetary dust.

Cat

Yeah, that's about as good as any, I suppose.These are, of course, just the largest ones. They are followed by (in various miscellaneous orders)

Dwarf planets, where not duplicated (e.g., Ceres = asteroid)

Other planetary moons

Asteroids

Trans Neptunian Objects (TNOs)

Meteoroids

Any categories I have missed, down to

Interstellar and interplanetary dust.

There may be some better designations at the IAU or with the Minor Planet folks, but IMO....

There is a consensus, I think, that a meteoroid is an object less than 1 meter. It's an asteroid or comet thereafter up to the size of about Ceres, which is a dwarf planet, a minor planet, and an asteroid.

Smaller than meteoroids are the micrometeoroids, which would be an equivalent to your note of "interplanetary dust", and "dust" is so much easier to say and type, so "micrometeoroids" is uncommon, no doubt.

For an astronomer, dust is pretty much any molecule greater than H2, usually, otherwise it's a gas.

Then there is a host of terms for regional activity, including Centaurs, Trans-Neptunian Objects (TNOs), Kuiper Belt Objects (KBOs) -- these are a subclass of TNOs, IIRC -- Scattered Disk Objects (SDOs) for the more distant objects.

Then there are those NEOs (Near Earth Objects):Amors, Apollos, Atrens and the Atiras.

Perhaps there will be names given for regions within the Oort Cloud once we can actually see some of these things. They are too dim for even the best scopes since their closest's distance is 10k AU.

Last edited:

Regarding the population distribution of objects while It will likely change given the number of objects but when I went through mass comparisons last year(because I was bored and you know 2020), though some had poor constraints and others lacked mass estimates at all, there does seem to be an interesting drop off in mass among solar system bodies after the 2 largest dwarf planets Eris and Pluto the largest known TNOs among the scattered disk and Plutino populations of the Kuiper belt as while both are fairly similar in size the 3rd most massive dwarf planet known Haumea a classical Kuiper belt object is only 1/3 the mass of Pluto the second most massive dwarf planet.

Given that the dwarf planets after that start dropping off rapidly in mass with Makemake roughly comparable in mass the the entire asteroid belt~3*10^21 kg, the next 3 Gonggong, Quaoar and Charon (if counted along with Pluto as a double dwarf planet as Charon is a bit more massive than Quaoar) all are roughly about half that (though Gonggong is a little bit more than half that) after that are smaller dwarf planets like Ceres Orcus and Salacia which are among solar system worlds (inclusive of the Sun) appear to be the 30th, 31st and 33rd most massive objects in the solar system.

As far as I can tell of the bodies lacking a moon to enable a reliable mass estimate radius wise only Sedna likely fits into the same category as above assuming a rock & ice composition.

So while we can expect the number of dwarf planets to increase those which are large are quite rare The more massive dwarf planets also have orbits that get closer to Neptune as you would expect if Neptune was what launched them there with any object that didn't subsequently get its orbit altered to no longer encounter Neptune getting further ejected/deflected/impacting or in the case of Triton getting captured.

I imagine that unless planet 9 exists there probably will not be many if any things quite in the mass range of the bigger dwarf planets at least within the Kuiper belt out beyond that we have no data so yeah.

Given that the dwarf planets after that start dropping off rapidly in mass with Makemake roughly comparable in mass the the entire asteroid belt~3*10^21 kg, the next 3 Gonggong, Quaoar and Charon (if counted along with Pluto as a double dwarf planet as Charon is a bit more massive than Quaoar) all are roughly about half that (though Gonggong is a little bit more than half that) after that are smaller dwarf planets like Ceres Orcus and Salacia which are among solar system worlds (inclusive of the Sun) appear to be the 30th, 31st and 33rd most massive objects in the solar system.

As far as I can tell of the bodies lacking a moon to enable a reliable mass estimate radius wise only Sedna likely fits into the same category as above assuming a rock & ice composition.

So while we can expect the number of dwarf planets to increase those which are large are quite rare The more massive dwarf planets also have orbits that get closer to Neptune as you would expect if Neptune was what launched them there with any object that didn't subsequently get its orbit altered to no longer encounter Neptune getting further ejected/deflected/impacting or in the case of Triton getting captured.

I imagine that unless planet 9 exists there probably will not be many if any things quite in the mass range of the bigger dwarf planets at least within the Kuiper belt out beyond that we have no data so yeah.

This Wiki article suggests that some estimates give up to 200 dwarf planets in the Kuiper Belt, which only extends to about 50 AU, and perhaps up to 10,000 thereafter, which is admittedly quite speculative.

Such distances not only make such objects very dim, they also must be monitored for very long periods to detect any motion. An object the size of, say, Sedna becomes invisible to even the HST when it is at aphelion (close to 1000 AU). Jupiter becomes invisible to the HST at about 11,000 AU, IIRC.

It will be interesting to see what we find over time as it may help us understand the planetary dynamics required to have tossed what we find out there.

Such distances not only make such objects very dim, they also must be monitored for very long periods to detect any motion. An object the size of, say, Sedna becomes invisible to even the HST when it is at aphelion (close to 1000 AU). Jupiter becomes invisible to the HST at about 11,000 AU, IIRC.

It will be interesting to see what we find over time as it may help us understand the planetary dynamics required to have tossed what we find out there.

Catastrophe

"Science begets knowledge, opinion ignorance.

This Wiki article suggests that some estimates give up to 200 dwarf planets in the Kuiper Belt, which only extends to about 50 AU, and perhaps up to 10,000 thereafter, which is admittedly quite speculative.

Such distances not only make such objects very dim, they also must be monitored for very long periods to detect any motion. An object the size of, say, Sedna becomes invisible to even the HST when it is at aphelion (close to 1000 AU). Jupiter becomes invisible to the HST at about 11,000 AU, IIRC.

It will be interesting to see what we find over time as it may help us understand the planetary dynamics required to have tossed what we find out there.

Absolutely spot on! The extremely succinct commentary we have come to expect from Helio.

Cat

Hello.. Greetings board first time poster here.

I am posing this question to the board . Why did the IAU make themselves the Gatekeepers of the IAU Dwarf Planet category, and then stop adding them? Was it just a political move to appease the Pluto crowd?

There is more than sufficient data to support Orcus, Quaoar, and Gonggong as "Official Dwarf Planets". They all have moons to help support their mass. Orcus, Quaoar, and Sedna were submitted over a decade ago by Dr. Tancredi for inclusion to the IAU. In actuality there is more data supporting the inclusion of Orcus and Quaoar than Haumea and Makemake.(Those two were just kind of thrown in as they were being named at the time).

Taxonomy matters in science, and in my eyes its not arbitrary what they are called. Those four objects should be added to the IAU Dwarf Planet list. The IAU made themselves the Gatekeepers of this process and threw away the keys!

I am posing this question to the board . Why did the IAU make themselves the Gatekeepers of the IAU Dwarf Planet category, and then stop adding them? Was it just a political move to appease the Pluto crowd?

There is more than sufficient data to support Orcus, Quaoar, and Gonggong as "Official Dwarf Planets". They all have moons to help support their mass. Orcus, Quaoar, and Sedna were submitted over a decade ago by Dr. Tancredi for inclusion to the IAU. In actuality there is more data supporting the inclusion of Orcus and Quaoar than Haumea and Makemake.(Those two were just kind of thrown in as they were being named at the time).

Taxonomy matters in science, and in my eyes its not arbitrary what they are called. Those four objects should be added to the IAU Dwarf Planet list. The IAU made themselves the Gatekeepers of this process and threw away the keys!

Catastrophe

"Science begets knowledge, opinion ignorance.

Helio, double click on your graph to see scales.

Does an object 0.000001 Earth mass really clear at 1 AU? In other words, should the vertical scale be 0 at 1 AU?

Cat

Does an object 0.000001 Earth mass really clear at 1 AU? In other words, should the vertical scale be 0 at 1 AU?

Cat

Catastrophe

"Science begets knowledge, opinion ignorance.

The questioner posted:

Quote

Why is Mercury's core big?

An alternative is that a larger Mercury was struck in its early life, during the violent, chaotic beginnings of the solar system. Such an impact could have stripped away much of its outer shell, leaving a core too big for remaining planet.

Quote

. . . . . . . . . and most of Mercury's mantle probably ended up in the Sun, together with a lot of what hit it.

Cat

I keep seeing articles about what should be a planet and what should be a dwarf planet. Looking at what the current rules are, a planet must have "cleared out neighborhood around its orbit". I would think that Mercury is a dwarf planet. I think that Mercury didn't clear its neighborhood, the Sun did. I would surmise that if Mercury was in Pluto's current orbit, the debris in and around the orbit would still be there.

Quote

Why is Mercury's core big?

An alternative is that a larger Mercury was struck in its early life, during the violent, chaotic beginnings of the solar system. Such an impact could have stripped away much of its outer shell, leaving a core too big for remaining planet.

Quote

. . . . . . . . . and most of Mercury's mantle probably ended up in the Sun, together with a lot of what hit it.

Cat

I keep seeing articles about what should be a planet and what should be a dwarf planet. Looking at what the current rules are, a planet must have "cleared out neighborhood around its orbit". I would think that Mercury is a dwarf planet. I think that Mercury didn't clear its neighborhood, the Sun did. I would surmise that if Mercury was in Pluto's current orbit, the debris in and around the orbit would still be there.

Those rules were actually the first ones actually defined, before that there were no rules except general consensus. For many years we thought Pluto was much larger than it is; Pluto and Charon appeared to be one body not much smaller than the earth. Now it also seems like most stars have planets, but very few resemble ours, most are very chaotic. As we find out more how small bodies work, I do not doubt that the ‘rules’ will change from time to time. Wouldn’t be surprised at all if some system has an earth size planet or even larger that is in a resonant orbit with another Jupiter somewhere.

Yep. People forget what the word "planet" means. If one of those tiny, bright objects moves relative to those that don't, it was a planet, to the ancient Greeks. The Sun and Moon were comfortably known as planets. When asteroids (coined by Newton) were discovered, they were moving, so they were first called planets.Those rules were actually the first ones actually defined, before that there were no rules except general consensus.

But we were taught in school differently because we learned that most weren't just points of light.

Fortunately, physics easily (kinda) addresses what mass is needed for any given orbital distance in order to say it "clears its orbit". The closer the would-be planet is to the host star, the less mass is required. Hence, Mercury, using physics, clears its orbit and by about 100x more than the mass needed.For many years we thought Pluto was much larger than it is; Pluto and Charon appeared to be one body not much smaller than the earth. Now it also seems like most stars have planets, but very few resemble ours, most are very chaotic. As we find out more how small bodies work, I do not doubt that the ‘rules’ will change from time to time. Wouldn’t be surprised at all if some system has an earth size planet or even larger that is in a resonant orbit with another Jupiter somewhere.

However, at 400 AU, even the Earth doesn't have enough mass to clear its orbit.

Jean-Luc Margot's paper.

Oops, I definitely missed this from a few months ago, I see. I think the scale is ok.Helio, double click on your graph to see scales.

Does an object 0.000001 Earth mass really clear at 1 AU? In other words, should the vertical scale be 0 at 1 AU?

At 1 AU, the clearing mass is 0.0012 Earth masses to clear the orbit around a solar mass star. This assumes, of course, a more massive body gives it that chance.

Catastrophe

"Science begets knowledge, opinion ignorance.

"cleared out neighborhood around its orbit"

There is definitely something wrong here. What about Trojan asteroids which share Jupiter's orbit, 60 degrees in front and behind Jupiter. And there are other "Trojans".

Cat

There is definitely something wrong here. What about Trojan asteroids which share Jupiter's orbit, 60 degrees in front and behind Jupiter. And there are other "Trojans".

Cat

I think perhaps the phrase should have been that a planet has control of objects in its orbital vicinity. Certainly Jupiter has its Trojans, but it has direct control of their behavior much as Neptune has direct control over the Pluto-Charon system. Any new object that drifts into Jupiter’s domain due to perturbations, Jupiter eliminates or takes control in short order like Shoemaker-Levy 9.

Catastrophe

"Science begets knowledge, opinion ignorance.

"Jupiter has its Trojans, but it has direct control of their behavior"

That's fine (really) if you include 60 degrees either side as "orbital vicinity". Maybe its the good old "common language" thing again? Orbital vicinity can mean either "in its orbit, and near it" or "near its orbit". I took the first, maybe you took the second. Neither is right or wrong. Just different interpretations.

Come back Korzybski!

Cat

That's fine (really) if you include 60 degrees either side as "orbital vicinity". Maybe its the good old "common language" thing again? Orbital vicinity can mean either "in its orbit, and near it" or "near its orbit". I took the first, maybe you took the second. Neither is right or wrong. Just different interpretations.

Come back Korzybski!

Cat

The Trojans only support why the physic’s model for “clearing” best defines planet hood. Jupiter is the king of clearing,. If those Trojans move out of their place, they will be tossed.

Catastrophe

"Science begets knowledge, opinion ignorance.

Sure because the object needed to do that will likely already be a star.P.S. if something large enough hits/merges Jupiter, can it still upgrade to star?

Similar threads

- Replies

- 0

- Views

- 276

- Replies

- 0

- Views

- 2K

- Replies

- 1

- Views

- 8K

- Replies

- 0

- Views

- 2K

TRENDING THREADS

-

Hubble Tension explained (including its value) by the two phase cosmology

- Started by Geoff Dann

- Replies: 210

-

New interpretation of QM, with new two-phase cosmology, solves 15 foundational problems in one go.

- Started by Geoff Dann

- Replies: 320

-

The birth of the Quantum Convergence Threshold (QCT):

- Started by Capanda Research

- Replies: 84

-

Basic Error: The accelerating Universe conclusion - reason

- Started by Gibsense

- Replies: 263

-

-

-

Latest posts

-

-

-

-

-

-

Question What happens when we pass through Interstellar Clouds?

- Latest: Harry Costas

-

Space.com is part of Future plc, an international media group and leading digital publisher. Visit our corporate site.

© Future Publishing Limited Quay House, The Ambury, Bath BA1 1UA. All rights reserved. England and Wales company registration number 2008885.