Reading about material to be tested at the ISS which is designed to provide external protection for structures in orbit or transiting to the Moon or Mars, or on the surfaces of the Moon or Mars. I understand that exposure to particles and radiation is a major threat to the health of the astronauts, especially as missions get even longer. A mission to Mars may last for years? (Could even be one way eventually?)

Question Does this material also reduce the amount of the radiation and cosmic particles the astronauts are exposed to?

- Thread starter RussellB10

- Start date

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

This coating will be installed on a panel "directly facing the Sun". The Sun is a source of UV and low energy particles. These are not an issue as far as humans are concerned, as they are absorbed by even a very thin layer of metal. It is damage to that metal that NASA is trying to fix.

The concern with human DNA damage in space is when outside the Van Allen Belts the high energy cosmic rays will cause a problem. ISS is inside those belts and not subject to them as much.

High energy cosmic rays are stopped only by low atomic weight barriers. The best low atomic weight atom is hydrogen. A thick layer of water, about 40 feet thick, would be needed to protect astronauts on long term missions. This is equivalent to what protects us on Earth. Plastics also work well. A magnetic field can be used to steer them away from the spacecraft.

High atomic weight barriers such as steel or lead work well against EM waves such as gamma rays, whose absorption is a function only of total mass in the shield, irrespective of atomic weight, but they don't work well against high energy particles. Those particles simply bounce from one high atomic weight atom to another, losing little energy and eventually come out inside the spacecraft unimpeded. Low atomic weight atoms recoil sufficiently to absorb some of the energy and make good absorbers of high energy particles.

The concern with human DNA damage in space is when outside the Van Allen Belts the high energy cosmic rays will cause a problem. ISS is inside those belts and not subject to them as much.

High energy cosmic rays are stopped only by low atomic weight barriers. The best low atomic weight atom is hydrogen. A thick layer of water, about 40 feet thick, would be needed to protect astronauts on long term missions. This is equivalent to what protects us on Earth. Plastics also work well. A magnetic field can be used to steer them away from the spacecraft.

High atomic weight barriers such as steel or lead work well against EM waves such as gamma rays, whose absorption is a function only of total mass in the shield, irrespective of atomic weight, but they don't work well against high energy particles. Those particles simply bounce from one high atomic weight atom to another, losing little energy and eventually come out inside the spacecraft unimpeded. Low atomic weight atoms recoil sufficiently to absorb some of the energy and make good absorbers of high energy particles.

Last edited:

Thinking about this further ... Hydrogen gas at high pressure may work? This may require very high pressures. Working with high pressure gas can be awkward. Hydrogen chilled to a liquid? Oh. that would require chilling to below 20K. Very awkward. None of this is practical. The 40 feet of water also seems difficult. Are there people working on some possibly quite obscure, but doable, solutions for this?

Water is a cheap, easy shield and can be used for drinking and temperature moderation. There would also be some shielding effect from the oxygen but I don't know how much. A cubic meter of water weighs 1,000 kilograms. Divided by atomic weight of water of .018 kg/mole we get 55,555 moles.

The equivalent amount of gaseous hydrogen (55,555 moles) put into a one cubic meter bottle and held at room temperature (293 K) will have a pressure = n R T = 55,555 x 8.3 x 293 = 1.35e8 Pascals which is 1336 atm or 19,600 psi. This is not a good option as a radiation shield for a human habitat.

Liquid hydrogen weighs 70 grams per liter so a cubic meter would be 70 kg, which is 70,000 moles. This would be 26% better as a shield but in order to contain it at a modest 15 psi, it would need to be chilled to 20 Kelvins. Perhaps in outer space with a 3 K background this might not be a problem. There would need to be around 10 meters of liquid outside the living area, which should be at least 10 meters in diameter, so the diameter would be around 30 meters. For a 30 meter diameter steel tank at 15 PSI the skin would only need to be about 1/8" thick. I think the biggest problem would be living inside such a cold liquid. There would have to be quite a bit of insulation, probably around a meter.

The equivalent amount of gaseous hydrogen (55,555 moles) put into a one cubic meter bottle and held at room temperature (293 K) will have a pressure = n R T = 55,555 x 8.3 x 293 = 1.35e8 Pascals which is 1336 atm or 19,600 psi. This is not a good option as a radiation shield for a human habitat.

Liquid hydrogen weighs 70 grams per liter so a cubic meter would be 70 kg, which is 70,000 moles. This would be 26% better as a shield but in order to contain it at a modest 15 psi, it would need to be chilled to 20 Kelvins. Perhaps in outer space with a 3 K background this might not be a problem. There would need to be around 10 meters of liquid outside the living area, which should be at least 10 meters in diameter, so the diameter would be around 30 meters. For a 30 meter diameter steel tank at 15 PSI the skin would only need to be about 1/8" thick. I think the biggest problem would be living inside such a cold liquid. There would have to be quite a bit of insulation, probably around a meter.

I am going to quibble with part of Bill's treatise on how radiation shielding works.

First, there are 2 types of radiation we need to consider. One is gamma rays, which are very high energy light photons, much higher energy than x-rays. These penetrate material about like you see light getting dimmer as it passes into muddy water. Heavy materials like lead are good at attenuating it, but its intensity falls off at a rate that depends on its remaining intensity, rather than going a fixed distance and stopping.

The other type of radiation in cosmic rays are charge particles like protons and alpha particles (which are the nuclei of atoms like hydrogen and helium) moving at extremely high velocities, near the speed of light. Because these particles have electric charge, they see "drag" as they penetrate matter and interact with the electrons in the matter. At their high energies, they even interact with the nuclei of the atoms in the shielding materials. The result is that these charged particles lose their energies over specific distances into matter, depending on how much energy they start with. And, that energy gets distributed to the other charged particles they have interacted with, sending those off at lower, but still very high speeds, where they also have interactions with other atoms electrons and maybe nuclei. So there is a cascading effect of secondary (and even tertiary) radiation particles around the track of a high energy cosmic ray. That is why they can cause a lot of damage to the chemistry (including the DNA and RNA) of living tissue.

To shield charge particle cosmic rays, using heavy materials like lead increased the amount of secondary radiation produces. Using mateials with hydrogen puts the energy into the protons (and electrons) of the hydrogen, which have the highest charge to weight ratio, and can be most easily stopped by interaction with other atoms in the shielding material. And, hydrogen rich materials are lighter to raise into orbit, so a good choice for shieldng of space ships.

See https://depts.washington.edu/physce...Erin Board Cosmic Radiation and Shielding.pdf

First, there are 2 types of radiation we need to consider. One is gamma rays, which are very high energy light photons, much higher energy than x-rays. These penetrate material about like you see light getting dimmer as it passes into muddy water. Heavy materials like lead are good at attenuating it, but its intensity falls off at a rate that depends on its remaining intensity, rather than going a fixed distance and stopping.

The other type of radiation in cosmic rays are charge particles like protons and alpha particles (which are the nuclei of atoms like hydrogen and helium) moving at extremely high velocities, near the speed of light. Because these particles have electric charge, they see "drag" as they penetrate matter and interact with the electrons in the matter. At their high energies, they even interact with the nuclei of the atoms in the shielding materials. The result is that these charged particles lose their energies over specific distances into matter, depending on how much energy they start with. And, that energy gets distributed to the other charged particles they have interacted with, sending those off at lower, but still very high speeds, where they also have interactions with other atoms electrons and maybe nuclei. So there is a cascading effect of secondary (and even tertiary) radiation particles around the track of a high energy cosmic ray. That is why they can cause a lot of damage to the chemistry (including the DNA and RNA) of living tissue.

To shield charge particle cosmic rays, using heavy materials like lead increased the amount of secondary radiation produces. Using mateials with hydrogen puts the energy into the protons (and electrons) of the hydrogen, which have the highest charge to weight ratio, and can be most easily stopped by interaction with other atoms in the shielding material. And, hydrogen rich materials are lighter to raise into orbit, so a good choice for shieldng of space ships.

See https://depts.washington.edu/physce...Erin Board Cosmic Radiation and Shielding.pdf

Stopping embrittlement is the goal here

www.newscientist.com

www.newscientist.com

And you want tight fits

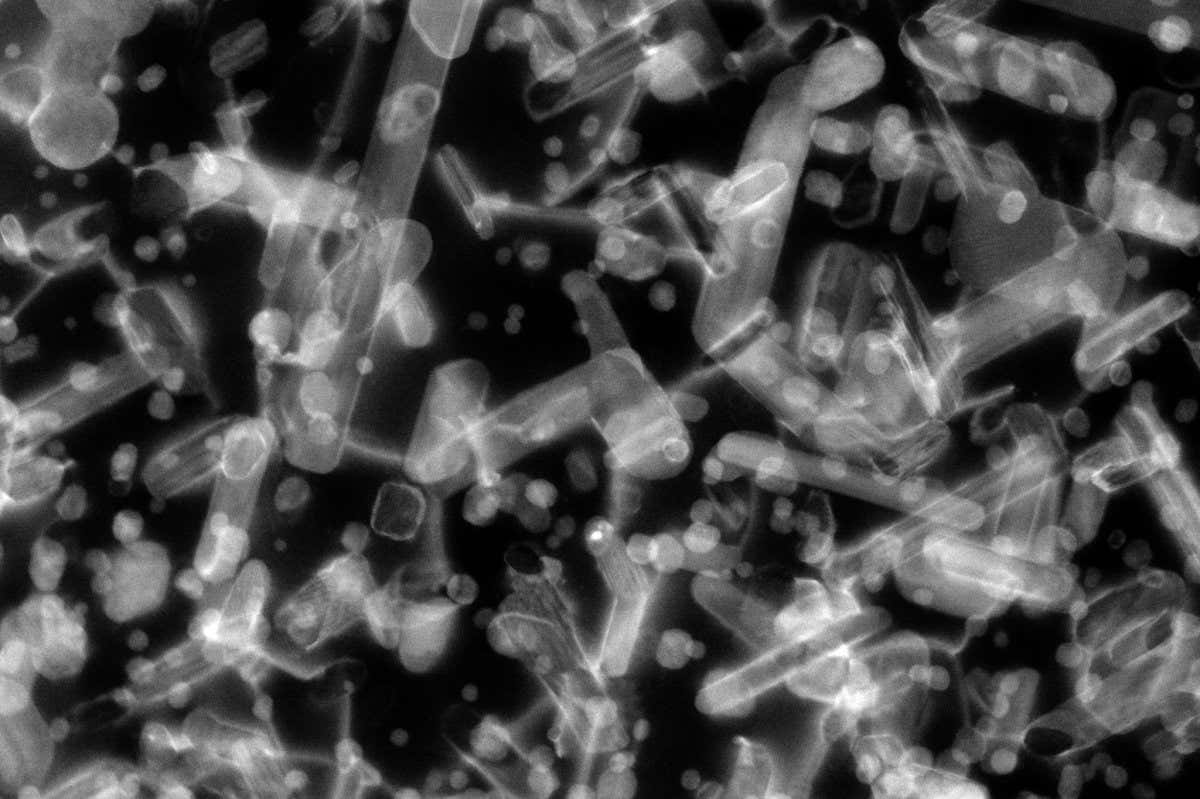

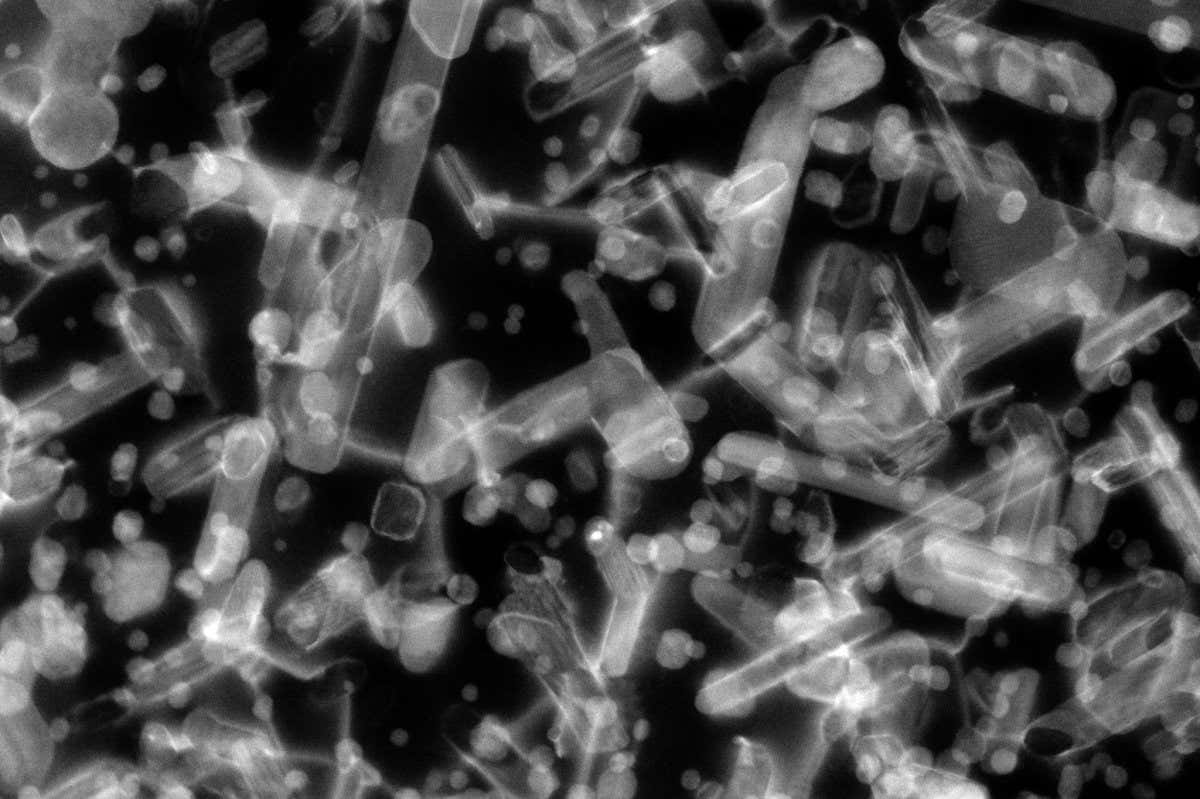

Aluminium alloy could boost spacecraft radiation shielding 100-fold

A new metal alloy keeps its flexibility and strength after high doses of radiation, making it potentially useful for building spacecraft or Mars colonies

And you want tight fits

Stopping embrittlement is the goal here

Correct. That is what the article is really about. But the editor put a title on it that says it would "boost shielding" by a factor of 100, which it actually does not do. It just lasts longer without coming apart.

It seems that too many current editors think of their jobs as primarily to generate "click bait" instead of making sure that the articles are clear, consise, and without gramarical errors or typos.

Similar threads

- Replies

- 26

- Views

- 5K

- Replies

- 1

- Views

- 1K

- Replies

- 3

- Views

- 2K

TRENDING THREADS

-

Question Does the Universe exist as a reality that is independent of observers?

- Started by whoknows

- Replies: 2

-

-

-

-

-

A Theory Suggesting Black Holes Don’t Just Swallow Matter, They Also Tear and Fling It Away – Looking for Feedback

- Started by adamator202

- Replies: 12

-

A Critical Examination of Cosmic Expansion and the Present-Day Origin of the CMB

- Started by Jzz

- Replies: 49

Space.com is part of Future plc, an international media group and leading digital publisher. Visit our corporate site.

© Future Publishing Limited Quay House, The Ambury, Bath BA1 1UA. All rights reserved. England and Wales company registration number 2008885.