E

WISE Mission Thread; Launched Dec 14

Page 3 - Seeking answers about space? Join the Space community: the premier source of space exploration, innovation, and astronomy news, chronicling (and celebrating) humanity's ongoing expansion across the final frontier.

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

- Status

- Not open for further replies.

E

EarthlingX

Guest

http://www.planetary.org : Progress on WISE's asteroid survey

May. 28, 2010 | 06:05 PDT | 13:05 UTC

By Emily Lakdawalla

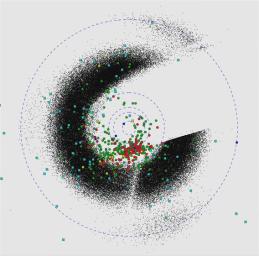

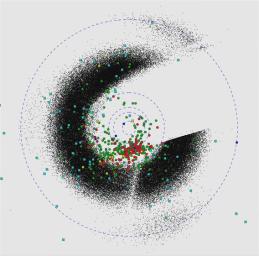

I wrote some time ago (last August, to be precise), about the expectations for the Wide-field Infrared Survey Explorer (WISE)'s contributions to solar system science. A couple of days ago, JPL posted an image and movie documenting the progress to date. Here's the plot:

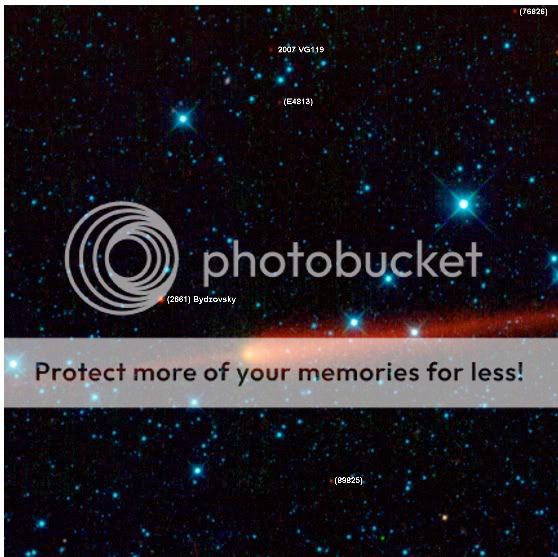

WISE's scan of 50% of the sky for asteroids and comets

This image shows asteroids observed as of May 24, 2010, by NASA's Wide-field Infrared Survey Explorer, or WISE. As WISE scans the sky from its polar orbit, more and more asteroids and comets are caught in its infrared vision. The mission had surveyed about three-fourths of the sky to date; however, data for only about 50 percent of the sky had been processed for asteroids and comets. Credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech / UCLA / JHU

The white dots show asteroids observed by WISE. Most of these are in the Main Belt between Mars and Jupiter, and some, the Trojans, orbit in a ragged bunch in front of, or behind, Jupiter. The red dots represent newfound near-Earth objects, which are asteroids and comets with orbits that come relatively close to Earth's path around the sun. The green dots are previously known near-Earth objects observed by WISE. The yellow squares show all comets seen by WISE so far.

As of May 24, 2010, WISE had seen more than 60,000 asteroids. Of those, 11,000 were new! Think about that -- more than one in six of the asteroids seen in WISE images had not been noticed before by Earth-bound observers. In addition, WISE had also observed more than 70 comets, 12 of which were new, and about 200 near-Earth objects, more than 50 of which were new.

Finally, I'd read an article on space.com indicating that Ned's proposal for a three-month extension for the WISE mission proposed to NASA at the seemingly modest cost of $6.5 million (roughly 2% of the nominal $320 million budget) had been rejected. This extension would have been run using only two of the four infrared detectors; the other two would require hydrogen coolant that will run out at the end of the nominal mission. I asked Ned what the hit of this rejection was to solar system science (which mostly means asteroid science). He told me, "the sensitivity of warm WISE to asteroids is much worse than the sensitivity of the full WISE with all four bands. For objects at 1 AU warm WISE is 2 times worse in sensitivity and for main belt objects it is 25 times worse. You really want longer wavelengths than the 4.6 micron cutoff of warm WISE, especially as you move out from the Sun and objects get cooler." The science payoff of a WISE mission extension would be for astronomical objects observed at shorter wavelengths.

E

EarthlingX

Guest

wise.ssl.berkeley.edu : May 24, 2010 - Heart and Soul Nebulae

F

Fomalhautian

Guest

M

MeteorWayne

Guest

Fomalhautian":2svituhg said:Interesting photo. So that dust trail encircles the sun?

No it doesn't. It's an effect of perspective.

From:

http://www.daviddarling.info/encycloped ... itail.html

Part of the dust tail of a comet that seems to point, often like a spike, toward the Sun. This rare phenomenon is an illusion caused by the viewing geometry and typically occurs when Earth crosses the plane of a comet's orbit when the comet is relatively close to the Sun. Under these circumstances, the cometary dust, which lies in a thin sheet and lags behind the comet, may be seen edge-on as an antitail. One of the most prominent antitails ever seen was that of comet Arend-Roland during its perihelion passage in 1957.

From:

http://www.aerith.net/comet/weekly/current.html

Comet 65P/Gunn (6.80 year period)

Now it is visible visually at 12.3 mag (May 22, Juan Jose Gonzalez). It will brighten up to 12-13 mag in summer. But it locates somewhat low in the Northern Hemisphere.

Date(TT) R.A. (2000) Decl. .... Delta .. r .. Elong. m1 Best Time(A, h)

June 5 ... 21 12.14 ... -26 34.6 1.830 2.510 121 12.9 3:01 (340, 26)

June 12 ..21 14.54 ...-27 10.4 1.772 2.520 127 12.9 2:59 (346, 26)

JPL sbdb page:

http://ssd.jpl.nasa.gov/sbdb.cgi?sstr=6 ... ;cad=1#cad

Gary Kronk's Cometography page:

http://cometography.com/pcomets/065p.html

F

Fomalhautian

Guest

I pulled this quote from the link above the picture:

So I'm thinking it might encircle the sun. But looking at the similarities between pictures of the anti-tail on Arend-Roland and the Gun comet, they look almost identical.

Just ahead of the comet is an interesting fuzzy red feature that makes it look something like a swordfish, or narwhal. This "sword," or dust trail, is made of dust particles that have previously been shed by 65/P Gunn as it orbits the sun. The dust is warmed by sunlight and glows in infrared light. Dust trails like this one often can encircle the sun, following the orbital path of the comet that produced it.

So I'm thinking it might encircle the sun. But looking at the similarities between pictures of the anti-tail on Arend-Roland and the Gun comet, they look almost identical.

M

MeteorWayne

Guest

The thing about dust ejected by comets is that it's only dense near perihelion where it is ejected on each orbit. After that, each particle takes it's own orbit. Those ejected in the opposite direction from the comet's motion move slower and are in smaller (and shorter period) orbits. Those ejected ahead move faster and are in larger (and longer) orbits. The only time the dust trails come together is near perihelion, but they will arrive at different times. So while there is a "dust trail" near the comet's orbit, except when near perihelion it's very dispersed.

Then various effects start to remove the smaller dust particles, such as the solar wind and the Poynting Robertson effect. So only close to the comet's perihelion is the trail dense enough to notice. For those trails where perihelion is near earth, when we plow through them we get our meteor showers.

There are one or two exceptions where objects have broken up and shed enormous amounts of dust, but are mostly larger particles of asteroidal origin..

Then various effects start to remove the smaller dust particles, such as the solar wind and the Poynting Robertson effect. So only close to the comet's perihelion is the trail dense enough to notice. For those trails where perihelion is near earth, when we plow through them we get our meteor showers.

There are one or two exceptions where objects have broken up and shed enormous amounts of dust, but are mostly larger particles of asteroidal origin..

F

Fomalhautian

Guest

E

EarthlingX

Guest

wise.ssl.berkeley.edu : V385 Carinae - Jumbo Jellyfish or Massive Star?

June 17, 2010

Some might see a blood-red jellyfish in a forest of seaweed, while others might see a big, red eye or a pair of lips. In fact, the red-colored object in this new infrared image from NASA's Wide-field Infrared Survey Explorer (WISE) is a sphere of stellar innards, blown out from a humongous star.

Image Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/WISE Team

The star (white dot in center of red ring) is one of the most massive stellar residents of our Milky Way Galaxy. Objects like this are called Wolf-Rayet stars, after the astronomers who found the first few, and they make our Sun look puny by comparison. Called V385 Carinae, this star is 35 times as massive as our Sun, with a diameter nearly 18 times as large. It's hotter, too, and shines with more than one million times the amount of light.

Fiery candles like this burn out quickly, leading short lives of only a few million years. As they age, they blow out more and more of the heavier atoms cooking inside them -- atoms such as oxygen that are needed for life as we know it.

The material is puffed out into clouds like the one that glows brightly in this WISE image. In this case, the hollow sphere showed up prominently only at the longest of four infrared wavelengths detected by WISE. Astronomers speculate this infrared light comes from oxygen atoms, which have been stripped of some of their electrons by ultraviolet radiation from the star. When the electrons join up again with the oxygen atoms, light is produced that WISE can detect with its 22-micron infrared light detector. The process is similar to what happens in fluorescent light bulbs.

E

EarthlingX

Guest

[youtube]http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=sJmCG9TG5Iw[/youtube]

WISE is orbiting the Earth at an altitude of 525 kilometers (326 miles), circling Earth via the poles about 15 times a day. A scan mirror within the WISE instrument is stabilizing the line of sight so that snapshots can be taken every 11 seconds over the entire sky. Each position on the sky is imaged a minimum of eight times, and some areas near the poles are imaged more than 1,000 times. After a one-month checkout period, the infrared surveyor spent six months mapping the whole sky. It then begins a second scan to uncover even more objects and to look for any changes in the sky that might have occurred since the first survey. This second partial sky survey will end about three months later when the spacecraft's frozen-hydrogen cryogen runs out. Data from the mission is released to the astronomical community in two stages: a preliminary release will take place six months after the end of the survey, or about 16 months after launch, and a final release is scheduled for 17 months after the end of the survey, or about 27 months after launch.

E

EarthlingX

Guest

http://www.jpl.nasa.gov : NASA's WISE Mission to Complete Extensive Sky Survey

SDC : Prolific NASA Sky-Mapper Finds 25,000 Hidden Asteroids

July 16, 2010

This image shows the famous Pleiades cluster of stars as seen through the eyes of WISE, or NASA's Wide-field Infrared Survey Explorer. The mosaic contains a few hundred image frames -- just a fraction of the more than one million WISE has captured so far as it completes its first survey of the entire sky in infrared light. Image credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/UCLA

PASADENA, Calif. -- NASA's Wide-field Infrared Survey Explorer, or WISE, will complete its first survey of the entire sky on July 17, 2010. The mission has generated more than one million images so far, of everything from asteroids to distant galaxies.

"Like a globe-trotting shutterbug, WISE has completed a world tour with 1.3 million slides covering the whole sky," said Edward Wright, the principal investigator of the mission at the University of California, Los Angeles.

Some of these images have been processed and stitched together into a new picture being released today. It shows the Pleiades cluster of stars, also known as the Seven Sisters, resting in a tangled bed of wispy dust. The pictured region covers seven square degrees, or an area equivalent to 35 full moons, highlighting the telescope's ability to take wide shots of vast regions of space.

To view the new image, as well as previously released WISE images, visit http://www.nasa.gov/wise and http://wise.astro.ucla.edu .

The first release of WISE data, covering about 80 percent of the sky, will be delivered to the astronomical community in May of next year. The mission scanned strips of the sky as it orbited around the Earth's poles since its launch last December. WISE always stays over the Earth's day-night line. As the Earth moves around the sun, new slices of sky come into the telescope's field of view. It has taken six months, or the amount of time for Earth to travel halfway around the sun, for the mission to complete one full scan of the entire sky.

"The eyes of WISE have not blinked since launch," said William Irace, the mission's project manager at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, Calif. "Both our telescope and spacecraft have performed flawlessly and have imaged every corner of our universe, just as we planned."

So far, WISE has observed more than 100,000 asteroids, both known and previously unseen. Most of these space rocks are in the main belt between Mars and Jupiter. However, some are near-Earth objects, asteroids and comets with orbits that pass relatively close to Earth. WISE has discovered more than 90 of these new near-Earth objects. The infrared telescope is also good at spotting comets that orbit far from Earth and has discovered more than a dozen of these so far.

WISE's infrared vision also gives it a unique ability to pick up the glow of cool stars, called brown dwarfs, in addition to distant galaxies bursting with light and energy. These galaxies are called ultra-luminous infrared galaxies. WISE can see the brightest of them.

SDC : Prolific NASA Sky-Mapper Finds 25,000 Hidden Asteroids

By Denise Chow

SPACE.com Staff Writer

posted: 16 July 2010, 02:56 pm ET

A prolific NASA sky-mapping telescope will complete its first full survey of the sky Saturday, having beamed back to Earth more than a million images of everything from asteroids and comets to distant galaxies – some previously unseen until now.

"The primary goal of the mission is to do an all-sky survey in the thermal infrared with much higher sensitivity than has ever been done before," Edward Wright, the principal investigator of the mission at the University of California, Los Angeles, told SPACE.com. "We're succeeding in that."

N

nimbus

Guest

E

EarthlingX

Guest

Next May ..

Until then they will release many images, like this one :

PIA13121: Seven Sisters Get WISE

Check this image in the highest resolution (linked under above image), and you will notice a lot of dim red spots between brighter stars. I had problem finding spot on this image without them, so i guess there will be plenty more red dwarves than just a dozen.

Until then they will release many images, like this one :

PIA13121: Seven Sisters Get WISE

Check this image in the highest resolution (linked under above image), and you will notice a lot of dim red spots between brighter stars. I had problem finding spot on this image without them, so i guess there will be plenty more red dwarves than just a dozen.

M

MeteorWayne

Guest

There is now a page at JPL with WISE asteroid (NEA+PHA) and comet discovery statistics.

These tables show discovery statistics for NEAs and comets discovered by NASA's WISE mission. The first small table shows the number of NEAs, PHAs (a sub-group of NEAs), and comets discovered to-date (within a day or two). The second table shows each object discovered, sorted by designation, with selected parameters describing the object's orbit.

Discovery Totals

NEAs: 100

PHAs: 15

Comets: 15

Total: 115

http://neo.jpl.nasa.gov/stats/wise/

These tables show discovery statistics for NEAs and comets discovered by NASA's WISE mission. The first small table shows the number of NEAs, PHAs (a sub-group of NEAs), and comets discovered to-date (within a day or two). The second table shows each object discovered, sorted by designation, with selected parameters describing the object's orbit.

Discovery Totals

NEAs: 100

PHAs: 15

Comets: 15

Total: 115

http://neo.jpl.nasa.gov/stats/wise/

M

MeteorWayne

Guest

Wide-Field Infrared Survey Explorer Mission Status

NASA's Wide-field Infrared Survey Explorer, or WISE, is warming up. Team members say the spacecraft is running out of the frozen coolant needed to keep its heat-sensitive instrument chilled.

The telescope has two coolant tanks that keep the spacecraft's normal operating temperature at 12 Kelvin (minus 438 degrees Fahrenheit). The outer, secondary tank is now depleted, causing the temperature to increase. One of WISE's infrared detectors, the longest-wavelength band most sensitive to heat, stopped producing useful data once the telescope warmed to 31 Kelvin (minus 404 degrees Fahrenheit). The primary tank still has a healthy supply of coolant, and data quality from the remaining infrared detectors remains high.

WISE completed its primary mission, a full scan of the entire sky in infrared light, on July 17, 2010. The mission has taken more than 1.5 million snapshots so far, uncovering hundreds of millions of objects, including asteroids, stars and galaxies. It has discovered more than 29,000 new asteroids to date, more than 100 near-Earth objects and 15 comets.

http://www.nasa.gov/mission_pages/WISE/ ... 00810.html

NASA's Wide-field Infrared Survey Explorer, or WISE, is warming up. Team members say the spacecraft is running out of the frozen coolant needed to keep its heat-sensitive instrument chilled.

The telescope has two coolant tanks that keep the spacecraft's normal operating temperature at 12 Kelvin (minus 438 degrees Fahrenheit). The outer, secondary tank is now depleted, causing the temperature to increase. One of WISE's infrared detectors, the longest-wavelength band most sensitive to heat, stopped producing useful data once the telescope warmed to 31 Kelvin (minus 404 degrees Fahrenheit). The primary tank still has a healthy supply of coolant, and data quality from the remaining infrared detectors remains high.

WISE completed its primary mission, a full scan of the entire sky in infrared light, on July 17, 2010. The mission has taken more than 1.5 million snapshots so far, uncovering hundreds of millions of objects, including asteroids, stars and galaxies. It has discovered more than 29,000 new asteroids to date, more than 100 near-Earth objects and 15 comets.

http://www.nasa.gov/mission_pages/WISE/ ... 00810.html

E

EarthlingX

Guest

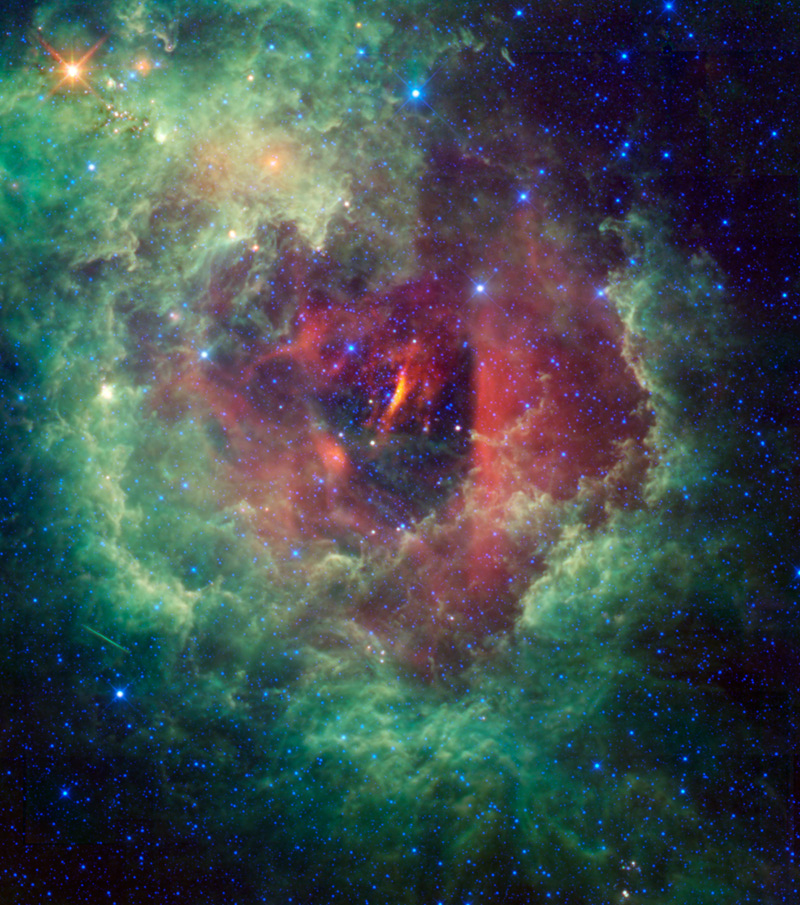

SDC : New Cosmic Photo Reveals Eye-Catching Rosette Nebula

wise.ssl.berkeley.edu : Aug 25, 2010 - WISE Captures the Unicorn's Rose

By SPACE.com Staff

posted: 27 August 2010

08:30 am ET

A NASA space telescope has snapped a stunning photo of a huge, flower-shaped cloud of dust and gas about 5,000 light-years from Earth.

The Wide-field Infrared Survey Explorer (WISE) captured the new cosmic photo of the star-forming Rosette nebula, which is in the constellation Monoceros (or Unicorn) in our Milky Way galaxy.

wise.ssl.berkeley.edu : Aug 25, 2010 - WISE Captures the Unicorn's Rose

Unicorns and roses are usually the stuff of fairy tales, but a new cosmic image taken by NASA’s Wide-field Infrared Explorer (WISE) shows the Rosette nebula located within the constellation Monoceros, or the Unicorn.

This flower-shaped nebula, also known by the less romantic name NGC 2237, is a huge star-forming cloud of dust and gas in the Milky Way Galaxy. Estimates of the nebula’s distance vary from 4,500 to 5,000 light-years away.

At the center of the flower is a cluster of young stars called NGC 2244. The most massive stars produce huge amounts of ultraviolet radiation, and blow strong winds that erode away the nearby gas and dust, creating a large, central hole. The radiation also strips electrons from the surrounding hydrogen gas, ionizing it and creating what astronomers call an HII region.

E

EarthlingX

Guest

wise.ssl.berkeley.edu : A Nebula by Any Other Name

There's more, including various image options and data.

Also slight change in WISE Discovery Statistics :

Sep 16, 2010

Nebulae are enormous clouds of dust and gas occupying the space between the stars. Some have pretty names to match their good looks, such as the Rose nebula, while others have much more utilitarian names. Such is the case with LBN 114.55+00.22, seen here in an image from NASA’s Wide-field Infrared Survey Explorer, or WISE.

Named after the astronomer who published a catalogue of nebulae in 1965, LBN stands for “Lynds Bright Nebula." The numbers 114.55+00.22 refer to nebula’s coordinates in the Milky Way Galaxy, serving as a sort of galactic home address.

Astronomers classify LBN 114.55+00.22 as an emission nebula. Unlike a reflection nebula, which reflects light from nearby stars, an emission nebula emits light. High-energy light blasted out from a nearby massive star strips away electrons from the nebula’s hydrogen gas, causing the gas to become charged. These nebulae are also called HII regions, with the “H” standing for hydrogen and the “II” indicating that the gas is ionized. As the ionized gas begins to cool from a higher-energy state to a lower-energy state, it glows. In the case of LBN 114.55+00.22, dust blocks the view of most of this nebula in visible light. But the dust of the nebula is also warmed by the light of the young stars within, and WISE’s infrared detectors see its beautiful infrared colors. Emission nebulae are usually found in the disks of spiral galaxies, and are places where new stars are forming.

In the lower left corner of the image is the bright red star IRAS 23304+6147, which is in the last phase of its life. As the hydrogen in its core burns out, the star will become a planetary nebula, ejecting material that absorbs visible light and glows in the infrared. This star’s name comes from the 1983 survey mission Infrared Astronomical Satellite (IRAS).

Another bright object in this image is the supergiant variable star HIP 117078, seen above and to the right of the nebula. In this case, HIP stands for Hipparcos, a European Space Agency satellite that catalogued the positions of over 100,000 stars.

The colors used in this image represent specific wavelengths of infrared light. Blue and cyan represent light emitted at wavelengths of 3.4 and 4.6 microns, which is predominantly from stars. Green and red represent light from 12 and 22 microns, respectively, which is mostly emitted by dust.

Image Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/WISE Team

There's more, including various image options and data.

Also slight change in WISE Discovery Statistics :

Discovery Totals

NEAs: 116

PHAs: 17

Comets: 16

Total: 132

E

EarthlingX

Guest

wise.ssl.berkeley.edu : Reflection Nebula DG 129 and Pi Scorpii

...Sep 21, 2010

In the Grip of the Scorpion’s Claw

Gripped in the claw of the constellation Scorpius, sits the reflection nebula DG 129, a cloud of gas and dust that reflects light from nearby, bright stars. This infrared view of the nebula was captured by NASA’s Wide-field Infrared Survey Explorer, or WISE.

Viewed in visible light, this portion of the sky seems somewhat unremarkable. But in infrared light, a lovely reflection nebula is revealed. DG 129 was first catalogued by a pair of German astronomers, named Johann Dorschner and Josef Gürtler, in 1963.

Much like gazing at Earth-bound clouds, it is fun to use your imagination when looking at images of nebulae. Some people see this nebula as an arm and hand emerging from the cosmos. If you picture the "thumb" and "forefinger" making a circle, it is as though you are seeing a celestial "okay" sign.

The bright star on the right with the greenish haze is Pi Scorpii. This star marks one of the claws of the scorpion in the constellation Scorpius. It is actually a triple-star system located some 500 light-years away. Perhaps a cross-species celestial handshake is imminent?

The colors used in this image represent different wavelengths of infrared light. The image was constructed from frames taken after WISE ran out of some of the coolant needed to chill its infrared detectors and began to warm up. The WISE detector sensitive to 22-micron light has become too warm to produce good images, but the three shorter wavelength detectors continue to crank out over 7,000 pictures of the sky every day, like the ones that make up this picture .Blue represents infrared radiation at 3.4 microns, while green represents light with a wavelength of 4.6 microns. Red represents 12-micron infrared light.

Image Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/WISE Team

3

3488

Guest

Interesting update.

This animation demonstrates how the Wide-field Infrared Survey Explorer, or WISE, surveys asteroids and comets in the solar system. The project to hunt for asteroids and comets -- including near-Earth objects, or NEOs -- using the WISE data is called NEOWISE.

The perspective shown here is loo......

Asteroid and Comet Census from WISE.

NASA/JPL-Caltech/UCLA/JHU.

Andrew Brown.

This animation demonstrates how the Wide-field Infrared Survey Explorer, or WISE, surveys asteroids and comets in the solar system. The project to hunt for asteroids and comets -- including near-Earth objects, or NEOs -- using the WISE data is called NEOWISE.

The perspective shown here is loo......

Asteroid and Comet Census from WISE.

NASA/JPL-Caltech/UCLA/JHU.

Andrew Brown.

M

MeteorWayne

Guest

From Andrew's link above:

"As of Oct. 4, 2010, the project has observed more than 150,000 main belt asteroids and discovered more than 33,500. It has observed 452 near-Earth objects and discovered 118. It has also observed 110 comets and discovered 19."

"As of Oct. 4, 2010, the project has observed more than 150,000 main belt asteroids and discovered more than 33,500. It has observed 452 near-Earth objects and discovered 118. It has also observed 110 comets and discovered 19."

3

3488

Guest

I agree Wayne, impressive set of statistics.

The frozen Hydrogen (Hydrogen Ice) coolant has run out & WISE has 'warmed' up. NASA will continue the mission using WISE at shorter IR wavelengths, enabling further comet & asteroid observations & discoveries, as well as the search for 'close' brown dwarves will continue, the possiblity that WISE could still find one or more closer than the Alpha Centauri system.

Andrew Brown.

The frozen Hydrogen (Hydrogen Ice) coolant has run out & WISE has 'warmed' up. NASA will continue the mission using WISE at shorter IR wavelengths, enabling further comet & asteroid observations & discoveries, as well as the search for 'close' brown dwarves will continue, the possiblity that WISE could still find one or more closer than the Alpha Centauri system.

Andrew Brown.

E

EarthlingX

Guest

Impressive mission, like an asteroid/comet vacuum cleaner

JPL article about WISE warming up, but still holding the post :

http://www.jpl.nasa.gov : NASA's WISE Mission Warms Up but Keeps Chugging Along

It's also used to help other missions :

http://www.jpl.nasa.gov : WISE Captures Key Images of Comet Mission's Destination

SDC : New Comet Photos Show Icy Target for NASA Probe

JPL article about WISE warming up, but still holding the post :

http://www.jpl.nasa.gov : NASA's WISE Mission Warms Up but Keeps Chugging Along

It's also used to help other missions :

http://www.jpl.nasa.gov : WISE Captures Key Images of Comet Mission's Destination

...October 05, 2010

This visitor from deep space, seen here by NASA's Wide-field Infrared Survey Explorer, or WISE, is comet Hartley 2 -- the destination for NASA's EPOXI mission. Image credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/UCLA

PASADENA, Calif. -- NASA's Wide-field Infrared Survey Explorer, or WISE, caught a glimpse of the comet that the agency's EPOXI mission will visit in November. The WISE observation will help the EPOXI team put together a large-scale picture of the comet, known as Hartley 2.

"WISE's infrared vision provides data that complement what EPOXI will see with its visible-light and near-infrared instruments," said James Bauer, of NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory, Pasadena, Calif. "It's as if WISE can see an entire country, and EPOXI will visit its capital."

WISE's infrared vision will allow the telescope to get a new estimate of the size of the comet's nucleus, or core, as well as a more thorough look at the sizes of dust particles that surround it. This information, when combined with what EPOXI finds as it gets closer to Hartley 2, will reveal how the comet has changed over time.

The WISE image is available at: http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA13438.

...WISE captured its view of the comet during an ongoing scan of the sky in infrared light. The mission has been busy cataloging hundreds of millions of objects, from comets to distant, powerful galaxies. In late September, it used up its frozen cryogen coolant as expected and began a new phase of its survey. Called the NEOWISE Post-Cryogenic Mission, it primarily focuses on finding additional asteroids and comets. To date, the WISE mission has observed more than 150,000 asteroids and 110 comets, including Hartley 2.

"Astronomers can reference our catalogue to get detailed infrared data about their favorite asteroid or comet," said Amy Mainzer, the principal investigator of NEOWISE at JPL. "Space missions can also use our observations for more information on their targets, as EPOXI is doing."

...Bauer said, "We want to know how the comet behaves as it comes toward the sun and out of deep freeze. The WISE image is one critical puzzle piece of many that will give a comprehensive view of the behavior of the comet through the time of the encounter."

The comet started to show signs of activity in the spring, spitting out gas and dust. By July, there were clear jets of gas. "Comparing the dust early on to what we see later with EPOXI helps us understand how the activity started on Hartley 2," said Michael A'Hearn, the principal investigator of EPOXI at the University of Maryland in College Park.

SDC : New Comet Photos Show Icy Target for NASA Probe

E

EarthlingX

Guest

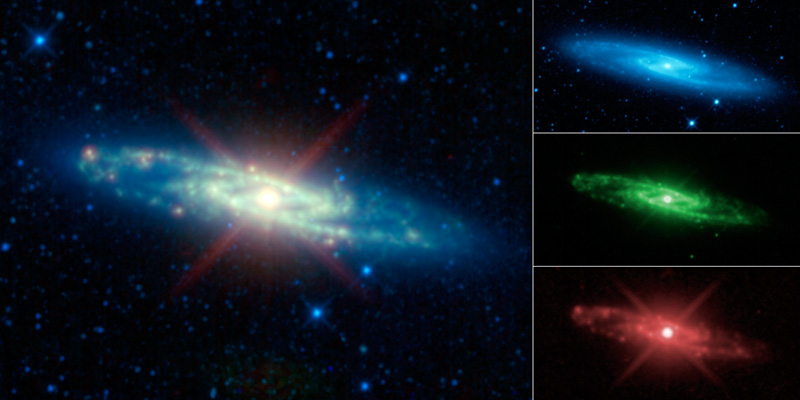

wise.ssl.berkeley.edu : The Many Infrared 'Personalities' of the Sculptor Galaxy

Oct 13, 2010

Image Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/WISE Team

The Sculptor galaxy is shown in different infrared hues, in this new mosaic from NASA's Wide-field Infrared Survey Explorer, or WISE. The main picture is a composite of infrared light captured with all four of the space telescope's infrared detectors.

The red image at bottom right shows the galaxy's active side. Infant stars are heating up their dusty cocoons, particularly in the galaxy's core, making the Sculptor galaxy burst with infrared light. This light -- color-coded red in this view -- was captured using WISE's longest-wavelength, 22-micron detector. The dusty burst of stars is so intense in the core that it generates diffraction spikes. Diffraction spikes are telescope artifacts normally seen only around very bright stars.

The green image at center right reveals the galaxy's emerging young stars, concentrated in the core and spiral arms. Ultraviolet light from these hot stars is being absorbed by tiny dust or soot particles left over from their formation, making the particles glow with infrared light that has been color-coded green in this view. WISE can see this light with a detector designed to capture wavelengths of 12 microns.

The blue image at top right was taken with the two shortest-wavelength detectors on WISE (3.4 and 4.6 microns). It shows stars of all ages, which can be found not just in the core and spiral arms but throughout the galaxy.

The Sculptor galaxy, or NGC 253, was discovered in 1783 by Caroline Herschel, a sister and collaborator of the discoverer of infrared light, Sir William Herschel. It was named after the constellation in which it is found, and is part of a cluster of galaxies known as the Sculptor group. The Sculptor galaxy can be seen by observers in the southern hemisphere with a pair of good binoculars.

NGC 253 is an active galaxy, which means that a significant fraction of its energy output does not come from normal populations of stars within the galaxy. The extraordinarily high amount of star formation occurring in the nucleus of this galaxy has led astronomers to classify it as a "starburst" galaxy. At a distance of approximately 10.5 million light-years away, NGC 253 is the closest starburst galaxy to our Milky Way Galaxy. However, the starburst alone cannot explain all the activity observed in the nucleus. One strong possibility is that a giant black hole lurks at the heart of it all, similar to the one that lies at the center of the Milky Way.

In late September of this year, after surveying the sky about one-and-a-half times, WISE exhausted its supply of the frozen coolant needed to chill the longest-wavelength detectors -- the 12- and 22-micron channels. The satellite is continuing to survey the sky with its two remaining detectors, focusing primarily on asteroids and comets. Read more about this survey, called the NEOWISE Post-Cryogenic mission, at jpl.nasa.gov.

E

EarthlingX

Guest

http://www.jpl.nasa.gov : Cool Star is a Gem of a Find

...November 09, 2010

That green dot in the middle of this image might look like an emerald amidst glittering diamonds, but it is actually a dim star belonging to a class called brown dwarfs. This particular object is the first ultra-cool brown dwarf discovered by WISE. Image credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/UCLA

NASA's Wide-field Infrared Survey Explorer, or WISE, has eyed its first cool brown dwarf: a tiny, ultra-cold star floating all alone in space.

WISE is scanning the whole sky in infrared light, picking up the glow of not just brown dwarfs but also asteroids, stars and galaxies. It has sent millions of images down to Earth, in which infrared light of different wavelengths is color-coded in the images.

"The brown dwarfs jump out at you like big, fat, green emeralds," said Amy Mainzer, the deputy project scientist of WISE at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, Calif. Mainzer, who makes jewelry in her spare time, explained that the brown dwarfs appear like green gems in WISE images because the methane in their atmospheres absorbs the infrared light that has been coded blue, and because they are too faint to give off the infrared light that is color-coded red. The only color left is green.

Like Jupiter, brown dwarfs are made up of gas -- a lot of it in the form of methane, hydrogen sulfide, and ammonia. These gases would be deadly to humans at the concentrations found around brown dwarfs. And they wouldn't exactly smell pretty.

"If you could bottle up a gallon of this object's atmosphere and bring it back to Earth, smelling it wouldn't kill you, but it would stink pretty badly -- like rotten eggs with a hint of ammonia," said Mainzer.

...WISE's new brown dwarf is named WISEPC J045853.90+643451.9 for its location in the sky. It is estimated to be 18 to 30 light-years away and is one of the coolest brown dwarfs known, with a temperature of about 600 Kelvin, or 620 degrees Fahrenheit. That's downright chilly as far as stars go. The fact that this brown dwarf jumped out of the data so easily and so quickly -- it was spotted 57 days into the survey mission -- indicates that WISE will discover many, many more. The discovery was confirmed by follow-up observations at the University of Virginia's Fan Mountain telescope, the Large Binocular Telescope in southeastern Arizona, and NASA's Infrared Telescope Facility on Mauna Kea, Hawaii. The results are in press at the Astrophysical Journal.

- Status

- Not open for further replies.

Similar threads

- Replies

- 0

- Views

- 415

- Replies

- 0

- Views

- 431

- Replies

- 0

- Views

- 381

- Replies

- 0

- Views

- 350

TRENDING THREADS

-

-

-

-

-

Tiny ‘primordial’ black holes created in the Big Bang may have rapidly grown to supermassive sizes

- Started by Admin

- Replies: 2

-

-

A Critical Examination of Cosmic Expansion and the Present-Day Origin of the CMB

- Started by Jzz

- Replies: 57

Space.com is part of Future plc, an international media group and leading digital publisher. Visit our corporate site.

© Future Publishing Limited Quay House, The Ambury, Bath BA1 1UA. All rights reserved. England and Wales company registration number 2008885.